Since the 1940s, optical engineers have attempted to design a lens that could focus without moving parts. The invention of the autofocus lens in 1977 and the proliferation of zoom lenses in the 1980s and 1990s coupled with the trend toward miniaturization have made mechanical lenses more expensive, complex, and delicate and have led to demands for a solution that requires no moving parts. At Photonics West (22-27 January 2005; San Jose, CA, USA), Varioptic (Lyon, France; www.varioptic.com) showed the first such lens, based on a process known as electro wetting.

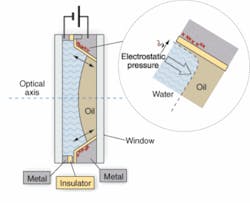

"To construct this lens," says Bruno Berge, president, "a water drop is deposited on a substrate made of metal, covered by a thin insulating layer." A voltage applied to the substrate modifies the contact angle of the liquid drop. The liquid lens uses two isodensity liquids, one of which is an insulator while the other is a conductor. The variation of the applied voltage leads to a change of curvature of the liquid-liquid interface, which in turn leads to a change of the focal length of the lens (see figure).

"To operate properly," says Berge, "the two liquids should have exactly the same density, and the optical axis should be stable," which allows the lens to work in every possible orientation. This is achieved by combining a mixture of dense and less-dense fluids and centering the liquid-liquid interface.

AUTOFOCUS CAPABILITY

Varioptic demonstrated the autofocusing capability of the lens. Coupled to the 1.3-Mpixel CMOS imager kit from Micron Technology (Boise, ID, USA; www.micon.com), the lens was shown focusing from 30 mm to infinity. To perform this autofocusing, captured images are analyzed by a single-chip image processor on the development board. Using an autofocus algorithm with edge-sharpness detection, the IC determines the extent to which the image is focused. These data are then transferred over a serial I2C interface to a driver that controls the voltage applied to the Varioptic lens.

With its response time of 2/100 s and power consumption of 0.5 mW, the lens will be initially targeted at digital still-camera applications, 1- or 2-D barcode analysis, and biometric identification systems such as iris and fingerprint recognition. According to Joshua Hong, business-development manager at Varioptic, the company has also developed a video-rate version of the lens capable of switching times of 30 ms or less. This will be offered to OEMs as demand dictates. Varioptic expects to produce the lens in quantity prices of less than €1/device.

OTHER PRODUCTS

Varioptic is not the first company to develop this type of lens. Last year, Stein Kuiper and Benno Hendricks of Philips Research (Eindhoven, The Netherlands; www.research.philips.com) demonstrated their FluidFocus technology at CeBIT. Measuring 3 mm in diameter by 2.2 mm long, the focal range of the system extends from 5 cm to infinity and switches over the full focal range in less than 10 ms. Controlled by a dc voltage, the lens has been tested with more than 1 million focusing operations without loss of optical performance.

Which company will make money producing these devices remains to be seen. In patent #WO 03/069380A1 of 21 August 2003, it is clearly stated that the Philips Research part cannot be considered novel or involve an innovative step when the document is taken alone. In the document, there are also clear references to patents held by Bruno Berge, relating to patents that date back as far as 1997 and 1998. "This," says Hong, "clearly implies that Philips was not the original inventor of the design."

Liquid lenses use two isodensity liquids, one of which is an insulator, the other a conductor. Varying the voltage between the water and the wall electrode leads to a change of curvature of the liquid-liquid interface, which in turn leads to a change of the focal length.