Spotlight on advanced technology Ship's data recorder tracks images from multiple sensors

By registering on-going radar, voice, and transducer information, a ship's data recorder provides permanent evidence of seafaring performance and problems.

By Andrew Wilson, EditorAccording to the Joint Accident Investigation Commission, the navigation computer of the ill-fated ferry Estonia, which contained a data-logging function and detailed information about its final sea voyage, could not be found aboard the sunken ship (see "Ferry sinks without a data trace," p. 44). A ground positioning-sensor receiver was recovered, but no information could be retrieved. No other information could be salvaged from all the ship's navigation and operations equipment.

"For years, flight-data recorders have been used by aircraft manufacturers to chronicle the behavior of on-board navigation and control systems," says Anders Jangö, technical manager with Consilium Navigation AB (Stockholm, Sweden). "Now, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) is planning the installation of a similar recorder to monitor the sailing performance of ships." Dubbed voyage data recorders (VDRs), these devices will monitor on-board video, radar, sonar, and other shipboard instruments to provide a permanent navigation record—a record that was sadly unavailable to investigators of the Estonia tragedy.

Already, the European Union has decided that all roll-on, roll-off ships and high-speed craft entering European ports should be equipped with VDRs. According to Jangö, the number of ships worldwide that will need to be equipped with such devices is between 40,000 and 50,000. To build such systems, vendors such as Consilium Navigation are turning to high-speed frame grabbers and other off-the-shelf PC-based data-acquisition boards to capture data from high-resolution radar systems, spoken communications, and transducers that measure a ship's speed, propeller data, and fire-alarm status.

Digitizing images

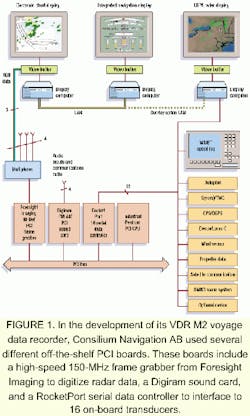

In the development of the Consilium VDR M2, data must be recorded simultaneously from a number of different sensors, including radar and video. To accomplish this, Consilium implemented the M2 with PCI off-the-shelf data-acquisition boards designed to digitize the different types of data (see Fig. 1).

"One of the requirements set out by the IMO was to record precisely the radar, navigation, and chart displays," says Jango. "Because each of these displays can be scrolled with off-screen memory resident in the display controller, the red, green, and blue (RGB) display data must be digitized when delivered as outputs from the on-board display computer," he says. To perform this digitizing, graphics screen buffers are placed between the display computer and the monitor so that the RGB signals can be routed though a multiplexer and then digitized.

To digitize the RGB signals, Consilium engineers chose the Hi-Def Accura frame-grabber board from Foresight Imaging (Chelmsford, MA). In operation, the Hi-Def Accura board provides four separate inputs to capture high-speed analog video signals. An important engineering decision that led to the choice of board was its input pixel or clock rate. As the board is programmable up to the 150 MHz, 1280 x 1024 x 85-Hz radar images (at a pixel clock frequency of 114 MHz) can easily be digitized. After the images are captured, they are stored in 4 Mpixel of on-board memory and then transferred to system memory across the PCI bus.

After images are transferred to a host PCI-based Pentium computer, PICTools from Pegasus Software (Tampa, FL) reduces the images to a series of JPEG compressed files. "PICTools is designed for programmers interested in low-level access to image compression and decompression functions, says Jangö, "and provides a low-level application programmers interface. The software tools perform well in memory-restricted or speed-intensive operations," he says. After compression, the images are saved from the PCI-based host computer to disk over a standard SCSI interface.

Sound and data

To obtain complete performance status on-board a ship at any point in a journey, the voices of officers on the bridge and the navigational sensor data must be digitized. In the design of the VDR M2, these data include the sound input from five microphones on the ship's bridge and one VHF communications channel. In this process, the sound channels are first routed via a mixing unit, and four audio channels are fed to a LCM440 multichannel sound card from Digigram (Arlington, VA).

Offering duplex operation with any combination of up to four active mono inputs and outputs, the LCM440 especially suits logging and sound-playback applications. "At a rate of 48 kHz," says Jangö, "this board performs real-time, simultaneous MPEG layer I and layer II compression and decompression during record and playback." When used in the VDR M2 system, the board compresses all four channels of audio data. The compressed audio is then transferred over the PCI bus under software control to the system hard drive.

To complete the design of the VDR M2, data from 16 sensors needed to be recorded simultaneously with the radar and audio data. These sensors monitor the ship's clock, position, speed, heading, depth, watertight-door-system status, and wind speed and direction. Because many of these sensors are interfaced to other ship computers using serial data transmission, Jangö decided to implement a PCI-based multiport serial controller (MSC) for interfacing to the ship's on-board sensors. Jangö and his colleagues chose the RocketPort 16 controller from Comtrol Corp. (Minneapolis, MN), an MSC with 16 serial inputs.

"Most serial cards use shared, dual-port memory, which can cause conflicts with other hardware and software products," says Jangö. "But because RocketPort is I/O memory-mapped to avoid shared-memory conflicts, configuration and port expansions are easier," he explains.

Because Consilium used standard, off-the-shelf products in the design of the VDR M2, it is possible, with the addition of faster analog frame grabbers and increased storage capacity, to record images larger than 1280 x 1024 pixels. Radar images could be captured about every 15 seconds and data recorded for as long as 12 hours. Now, the system is capable of displaying radar images every 15 seconds and voice and sensor data are recorded in real time (see Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. Radar display systems such as those available from Consilium can show large amounts of information on a single screen. Text and radar information are superimposed in green on radar echoes (left). An automatic radar-plotting aid can track 400 radar targets simultaneously. Transducer information displaying information on the ship's rate of turn, degrees per turn, draft, air pressure, and direction can also be displayed (right). Simultaneously, the display system is capable of replaying six channels of audio data.

Although the VDR developed by Consilium is capable of recording radar, voice, and sensor data, navigation requirements set down by the IMO require that such data be easily accessed in case of a ship's emergency. "On a ship," says Jangö, "there are two major types of emergencies—fire and water." And, unlike an aircraft tragedy, these generally do not occur in a few moments, but in minutes or hours."

Recognizing these factors, the IMO has specified that data must withstand some stringent environmental tests. These include a 50-g shock, a penetration test of a 100-mm steel pin of 250 kg falling from a 3-m height, fire tests of up to 1100°C, and water immersion of 30 days at a 6000-m depth.

To save data recorded by the VDR under such conditions, the IMO proposes the use of a "capsule" that is linked to the VDR. Easily recoverable in case of a ship's disaster, the Consilium capsule, equipped with an acoustical pinger, will be designed as a separate fire- and water-retardant unit. It will be linked over an Ethernet cable to the host VDR. By updating radar, acoustic, and transducer information periodically, the flash-memory-filled capsule will likely be located on the ship's mast to minimize its susceptibility to fire, water, and mechanical shock.

When installed on the thousands of ships now in service worldwide, it is likely that such voyage-data recorders will be used in a manner similar to flight-data recorders on aircraft. With this approach, seafaring travel will be safer and ship design, construction, and maintenance more reliable.

Ferry sinks without a data trace

At 7:00 pm on Sept. 27, 1994, the Estonia left the Port of Tallinn with 803 passengers and 186 crew on-board. The ferry was bound for Stockholm, Sweden, at a scheduled arrival of 9:30 the next morning. It never arrived. During the night, rough weather and heavy rain, high winds, and waves up to 5 m high smashed into the Estonia.

As the ship steered 35 km south east of Utö Island in the outer region of the Turku archipelago, the bow visor was torn off by wave pressure, and waves impacted the forward ramp. Latching mechanisms were unlocked and the forward ramp opened, allowing water to rush onto the car deck. After the visor's attachments failed, waves hit the upper edge of the car ramp, breaking its ramp locks. Within minutes, the visor and car ramp fell forward, leaving the ramp fully open. Vast amounts of water roared over the car deck. As the visor fell, it collided with the bow of the vessel. The ship took on a heavy starboard list, turned to port, and slowed down.

As the list to starboard increased, water entered the accommodation decks. Flooding continued at raging speed, and the starboard side of the ship submerged at about 1:30 am. During the final stage of flooding, the ferry listed sharply. The Estonia then sank quickly, stern first, and disappeared from local radar screens at about 1:50 am. A total of 852 persons lost their lives; 757 persons remain missing.

Company Information

Foresight Imaging

Chelmsford, MA 01824

Web: www.foresightimaging.com

Comtrol Corp

Minneapolis, MN 55311-3646

Web: www.comtrol.com

Consilium Navigation AB

Stockholm, Sweden

Web: www.consilium.se

Digigram

Arlington, VA 22201

Web: www.digigram.com

Pegasus Software

Tampa, FL 33607

Web: www.pegasustools.com