3D imaging, line-scan cameras and sensors are combined to optimize lumber quality.

Manufacturers of forest products such as lumber rely on machine vision systems to help optimize the cutting process, while maximizing profits. Characteristics such as knots, bark, voids, splits, checks, decay, resin, discolorations and grain formations impact the strength, durability, manageability and appearance of the wood material. Consequently, the lumber's usability and final value ultimately depend upon these characteristics.

Figure 1: COMACT's custom-built wood inspection system combines machine vision-based grade and yield optimization so that lumber mills can optimize product value based on current market pricing.

By accurately identifying the surface features, geometry and internal flaws that have the greatest impact on the value of lumber produced, and then guiding the production process based on current market pricing, machine vision systems can help producers maximize the value of the lumber they produce. To do this, machine vision and image processing systems are often used to:

• Measure three-dimensional shape, warp, wane, and variations inthickness

• Identify surface knots, holes, splits, decay, discoloration, and slope ofgrain

• Detect internal voids, knots, and decay.

Deployed at many stages of the process, machine-vision and image-processing systems perform various tasks such as evaluating rough logs to maximize lumber yield. They can also be used for inspecting rough-cut boards so that only good product takes up valuable dryer space, for optimization of edger, trimmer and planer nodes of lumber processing, as well as for grading trimmed lumber according to industry standards before shipping to market.

Understanding how the latter impacts sawmill profits, wood inspection and optimization equipment manufacturer COMACT (Saint-Georges, QC, Canada; www.comact.com) has recently upgraded the technology in its wood grading machines to include Linea line scan cameras from Teledyne DALSA (Waterloo, ON, Canada; www.teledynedalsa.com).

Figure 2: COMACT's custom software interface allows lumber mills to grade planks to an international standard.

The GigE Vision 26 kHz (4k) Linea line scan cameras feature CMOS sensors with a 7.04 μm pixel size that, according to Patrick Farley, hardware development leader at COMACT, increases resolution enough to detect very small splits that could not be detected with the previous cameras. "It's easier to do great image processing when you have nice clean images," Farley explains, "and that's what Teledyne DALSA cameras give us."

The new equipment, dubbed GradExpert 2.0, allows saw mills to automatically inspect and grade up to 300, 24-foot planks per minute, which is much faster than manual inspection and provides significant increases in throughput, according to Farley.

"The machines can operate pretty much unmanned, which is how the vast majority of our customers use them," says Farley. "Unlike human operators, the machine never gets tired and is consistently accurate plank after plank, letting sawmills redeploy their human resources to higher value tasks while increasing their grading accuracy and profitability. Further, it identifies imperfections to within 10/100,000 of an inch or 10 mils and, it does so with accuracy rates in the high 90s using COMACT's proprietary software algorithms."

Imaging and handling

Cost effectiveness because the large number of cameras required, and Ethernet connectivity to remote host computers for image processing were also desired camera features. "Since the material handling system conveys boards transversely through the grader, imaging each two-foot length of board requires approximately four cameras, one for each face, or 40 cameras for a system designed to grade 20-foot long planks," notes Farley.

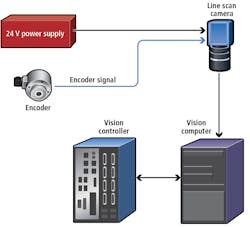

Figure 3: Line scan cameras from Teledyne DALSA are used to provide 360° inspection of lumber with each vision controller processing image data from up to eight cameras to make grading decisions that can be used to guide automated edging and trimming systems.

Acquired image data generated by the cameras is transmitted via Ethernet cables through switches to the memory of remote industrial PCs (iPCs) for processing. Each iPC can process image data from up to eight cameras. After image pre-processing functions, the iPC processes image data to extract the necessary information to not only make a decision about the grade of the lumber being scanned, but also to make decisions that are used to guide automated edging and trimming systems that accept board image data as input.

First, proprietary software algorithms identify all the major grading defects, their size and location. Then, based on this defect information, along with knowledge of the lumber-grading rules and current pricing data, edging and trimming solutions can automatically be generated to guide the cutting operations and maximize profit.

However, identifying defects in heterogeneous material such as wood and other organic products tends to be more challenging in many instances than identifying defects in parts made of more homogeneous materials such as metals and plastics in automotive or consumer electronics applications where defects encountered generally stand out more.

Having said that, many defects in wood material may only differ very slightly in appearance from clear wood, and such defects are not as easily defined or identified. Consequently, Farley notes that the color cameras are just one of numerous sensing technologies used on the lumber grading equipment.

"We mix and match sensor technologies to detect things such as surface roughness, blonde knots, and thickness changes in the wood that may not readily show up in the images acquired by the color cameras," explains Farley.

For example, each piece of wood passing through the grader is also scanned by Gocator 250 multi-point profile scanners from LMI Technologies (Burnaby, BC, Canada; www.lmi3d.com), and a custom photocell-based light curtain very quickly and accurately measures the length and width of each board, while simultaneously detecting edge defects.

Custom enclosures

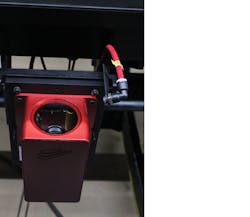

Due to environmental conditions in saw-mills such as dust and the risk of high velocity impact from wood being processed, COMACT engineers design and manufacture their own custom camera enclosures and LED lighting.

"Commercially-available camera enclosures didn't provide the protection we needed, or the mounting flexibility we required," explains Farley. "So we developed our own camera enclosure which is machined from a single block of aluminum to a thickness of at least a quarter of an inch."

The enclosure includes RJ-45 connectors, camera mounts and space to mount a heater element designed to keep electronics within the proper operating temperature range for equipment deployed in unheated sawmills.

Likewise, explains Farley, commercially-available lights didn't meet their requirements in terms of robustness. Consequently, COMACT engineers designed their own modular LED illumination solution, which reduces costs and achieves a much more rugged and flexible design.

"We sell systems that grade lumber from two to twenty-four feet long," explains Farley. "So our modular design consists of two-foot LED sections that can easily be connected to achieve the desired length for any particular piece of equipment we make."

Figure 4: COMACT manufactures its own custom camera enclosures that includes RJ-45 connectors, camera mounts and space to mount a heater element designed to keep electronics within the proper operating temperature range for equipment deployed in unheated sawmills.

Return on investment

Wood appearance guidelines based on an industry scale of "perfect" 0 for upscale applications, #1 for strength or highly-visible areas such as decks and fences, #2 for use within walls and #3 for economy applications must be followed, explains Farley. Otherwise, there are likely to be serious implications from both regulatory and customer service standpoints.

In addition to customer dissatisfaction, he explains, a sawmill that grades more than 5% #2 grade planks as the superior, cleaner #1 grade, faces the risk of losing their license or their right to sell a particular grade. Adding to the challenge is the fact that human graders may have mere seconds to examine both sides of a 24-foot plank and decide. "It's not unusual for sawmills to err on the side of caution and rate many higher quality #1 planks as #2 grade just to be on the safe side," says Farley. "This is costing them money every day."

Figure 5: Due to environmental conditions in saw-mills such as dust and the risk of high velocity impact from objects, COMACT engineers designed a custom LED illumination solution that reduces costs and provides a much more rugged and flexible design.

However, as valuable as automated wood inspection systems might be in this regard, perhaps potentially even more profitable for sawmills are COMACT's automated optimization capabilities. Sawmills can, for example, take #2 graded planks, and using the company's machines and proprietary algorithms, calculate how much grade #1 material they could reclaim from cutting the most profitable combination of different sized planks.

"Customers are taking a closer look at their own production, and even buying #2 graded bundles on the open market and optimizing and reselling them, driving substantial profits," explains Farley. "The machine can easily pay for itself in 6-12 months."

Companies mentioned:

COMACT

Saint-Georges, QC, Canada

www.comact.com

LMI Technologies

Burnaby, BC, Canada

www.lmi3d.com

Teledyne DALSA

Waterloo, ON, Canada

www.teledynedalsa.co

About the Author

John Lewis

John Lewis is a former editor in chief at Vision Systems Design. He has technical, industry, and journalistic qualifications, with more than 13 years of progressive content development experience working at Cognex Corporation. Prior to Cognex, where his articles on machine vision were published in dozens of trade journals, Lewis was a technical editor for Design News, the world's leading engineering magazine, covering automation, machine vision, and other engineering topics since 1996. He currently is an account executive at Tech B2B Marketing (Jacksonville, FL, USA).

B.Sc., University of Massachusetts, Lowell