Vision system inspects cereal and snack labels at high speeds

In the past,optical character recognition (OCR) vision systems were not traditionally thought of as fast, flexible, or maintainable. Today’s systems are different, so when a worldwide, top manufacturer of cereal and snack products tasked EPIC Machine Vision Systems (EPIC; St Louis, MO, USA; www.epicvisionsystems.com) with installing one, the vision systems integrator was confident in itsapproach.

At the manufacturer’s site, a system rejects from the conveyor packaged food products with incorrectly printed data codes. While the previous system worked reasonably well, it was old and unsupported by the originalsoftware developer. The manufacturer sought to upgrade this system to meet new quality standards and industry food-safety standards, and to improve the overall OCR process. The design team began with a front-end engineeringmethodology that involved gathering tens of thousands of in-process online images from multiple stock-keeping units (SKU), printers, and printing formats fortesting.

“We spend more time on the front end to ensure that the final turnkey vision system is not an object of the constant ‘tweaking’ that is all too common with many vision systems,” says EPIC’s Director of Engineering, DanNadolny.

A Teledyne DALSA Genie Nano M1940 GigE Vision monochrome camera captures images of OCR codes on food packaging.Image courtesy of Epic Systems

To install an OCR system for the company—which has more than 50 manufacturing facilities worldwide—EPIC used the SureDotOCR tool in Matrox Imaging Library (MIL) software fromMatrox Imaging (Dorval, QC, Canada; www.matrox.com/imaging) which is designed for reading dot-matrix text. With support from Matrox Imaging, EPIC used these image sets to optimize the algorithm parameters and establish a baseline for the necessary processing and imaging hardware. Test results included multiple printers and large amounts of print variation (e.g. contrast, aspect ratio, line positions, character spacing, and curvedlines.)

For the camera, EPIC selected a Genie Nano M1940 GigE Vision camera from Teledyne DALSA (Waterloo, ON, Canada;www.teledynedalsa.com). The M1940 camera is a monochrome model with a 2.4 MPixel IMX174 CMOS sensor from Sony (Tokyo, Japan; www.sony.com). The camera was set up to provide a 5-pixel dot diameter and a Matrox Indio I/O and communication PCIe board, which offers a GigE port with Power over Ethernet (PoE) support and 16 real-time, discrete digital I/O.

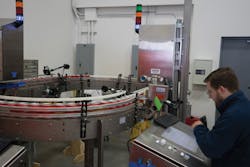

The machine vision system uses standard and industrial PCs, with a camera and dome “cloudy day” lighting providing uniform lighting across the product surface contrast. The goal was to achieve a 99.97% read rate, or a failure rate of less than 300 parts/million.

“The SureDotOCR algorithm met a 99.90% read rate, with one dot diameter setting and 99.99% read rate with three read attempts of different dot diameter settings,” says Chris Walker, EPIC Project Leader. “The ‘Dot Diameter’ is defined as the average pixel diameter of the individual dots in the dot-matrix printed textstring.”

He continues, “Matrox recommends a 7-pixel dot diameter, but the design team settled at a 5-pixel dot diameter to reduce image storage and bandwidthrequirements.”

Typical inspection times for a single read attempt—involving two lines of text and approximately 36 characters total—were around 40 ms, accordingtoWalker.

“Foreign font files were created and tested with similar performance ability as standard English alphanumeric fonts,” he says. “The algorithm was capable of exceeding 1200 inspections/minute on two lines of text with about 36 printed characters total. Read rates as high as 2500 inspections/minute were seen at single-read attempts. MIL-supported multi-threading and multi-core processing helped achieve the required readrates.”

The OCRvision system was designed and developed by Epic Systems to inspect alphanumeric codes on food packaging. Image courtesy of Epic Systems.

An inspection rate of 1200 parts/minute provides a consecutive inspection time of only 50 ms/part. The average inspection time for a single read attempt was just under this value at 40 ms. Three read attempts/inspection are recommended to increase system robustness. Inspection times periodically exceeded 100 ms and were even as high as 286 ms during early testing. The vision system had to rely on the multithreading architecture feature—a key feature supported by the MIL SDK—to overcome these times. Multithreading is synonymous with parallel processing and is the function by which a computer can concurrently perform multipleprocesses.

The machine vision system—through MIL—can also receive and buffer images for processing in a queue and have multiple threads process those images in parallel. While the multithreading architecture works well at meeting high-processing rates, this requires the vision system to keep track of the parts under inspection to properly reject failed parts subject to potentially longer inspectiontimes.

For example, if parts are traveling on a conveyor and the machine vision system starts to back up with a large queue of images to process, or if a read takes a significantly long time to process, the part waiting for an inspection result will be significantly further along the conveyor belt by the time the inspection is complete and the pass/fail result is ready. For this application, if a single read took 500 ms to process the part, it would be nearly 1 m further along theconveyor.

A sampleof the monochrome image captured by the vision system showing the codes printed the top of a snack food package. Image courtesy of Epic Systems.

Providing encoder feedback for the existing line conveyor, to track part distances from the point of inspection to an ejector located 1.5 m away, overcame this challenge, allowing the vision system to work with occasional issues of significantly long read times while guaranteeing that the inspection result would be communicated before the part reaches theejector.

In the end, the optical character recognition solution was flexible and robust enough to meet the application requirements, according toWalker.

About the Author

James Carroll

Former VSD Editor James Carroll joined the team 2013. Carroll covered machine vision and imaging from numerous angles, including application stories, industry news, market updates, and new products. In addition to writing and editing articles, Carroll managed the Innovators Awards program and webcasts.