Unlocking the Next Generation of LiDAR with Programmable Optics

Key Highlights

- Traditional LiDAR systems rely on mechanical parts, limiting their size, reliability, and adaptability in dynamic environments.

- Programmable optics, such as active metasurfaces, enable software-controlled beam steering and shaping without moving parts, leading to more compact and flexible sensors.

- Software-defined LiDAR allows for dynamic adjustment of scan patterns, field of view, and range, optimizing perception based on environmental context and task requirements.

- Real-world applications like autonomous mobile robots benefit from programmable sensing by adapting to lighting changes, reflective surfaces, and uneven terrains in real time.

For more than a decade, LiDAR systems have seen growing interest and use cases but adoption has been slow due to large size, high costs, and unscalable performance. The innovation in this space has largely been driven by improvements in the receivers which have become higher resolution, more sensitive and more integrated. But despite these advances, sensing systems still fall short in dynamic environments like warehouses or urban streets, where perception needs vary moment to moment. Next generation physical AI enabled applications require sensing that is solid-state, efficient, and software-defined, without increasing system size, cost, or complexity.

The bottleneck today is no longer in the receiver. It’s in the transmitter and in its rigidity. Most LiDAR systems can only project light in a fixed pattern, regardless of what the environment or application actually needs. With only traditional optics like bulk mirrors and lenses in their toolkits, lidar designers have been forced to take the brute force approach of either mounting the transmitter board on a rotor (spinning LiDAR) or steering the output beam of the transmit board using a moving polygon or MEMS mirror. As a result, the traditional LiDAR modules have not only been bulky, expensive and unreliable, but also static in performance given the mechanical mechanisms.

The software-defined solid-state LiDAR needs a transmitter that is reconfigurable capable of altering beam shapes, scan patterns, and field of view through software, without any moving parts. It allows lasers and optics to be differentiated from fixed hardware constraints and offers a flexible sensing paradigm where software-defined behaviors, such as beam splitting, region-of-interest scanning, and dynamic range control, become adjustable in real-time.

A Real-World Use Case: Why Programmable Sensing Matters to Robotics

Autonomous Mobile Robots (AMRs), especially those deployed in mixed indoor-outdoor settings, face a uniquely hard perception challenge. From dark-painted objects and reflective floor surfaces to sudden lighting changes, standard sensors fail to deliver consistent perception. And when perception breaks down, so does the robot’s productivity.

Programmable optics address the following real-world scenarios:

- Dynamic Environments: Different lighting, reflective surfaces, and occlusions (e.g., forklifts, boxes, glass, sunlight) in warehouses cause legacy sensors to miss or misinterpret objects. Programmable sensors can respond to these changes in real time.

- Slopes, Ramps, and Variable Floors: As robots climb slopes or navigate uneven flooring, the vertical orientation of perception must adapt. Software-defined sensors adjust ROI and integration parameters on the fly.

- Mixed Indoor-Outdoor Use: For logistics bots that traverse loading bays or warehouse perimeters, sensors must adapt to both indoor lighting and outdoor sunlight—something standard lidars and depth cameras often fail at.

- Perception-as-Learning: Just like our eyes and brains co-adapt to the environment, programmable optics enable closed-loop optimization where the system adjusts its sensing strategy dynamically based on accumulated experience or mission context.

- Aging and Lifetime Optimization: Over time, laser diodes and sensor sensitivity degrade. But an AI model, given adaptable optics, can tune operation to maintain usable performance—extending the lifetime and reducing total cost of ownership.

The benefits of programmable 3D sensing extend well beyond hardware simplification:

- Increased Speed: Longer range and precise detection allow faster robot movement without sacrificing safety.

- Higher Precision: Dynamic control of region-of-interest (ROI) enables high-res detection of pallets, humans, and reflective/dark materials.

- Improved Safety & Collaboration: Better point cloud fidelity reduces false positives and allows tighter operation near humans or other robots.

- Less Downtime: Reduced failures from environmental artifacts means fewer human interventions.

In aggregate, these benefits enable higher throughput, better resource utilization, and lower operational risk—key KPIs for robotic deployments in warehouses, manufacturing, logistics, and even healthcare environments.

A New Sensing Paradigm

Traditional LiDAR systems are controlled through either mechanical rotation or fixed-pattern flash illumination technology. While this makes the system optimized for single use cases, it also means the system cannot be adjusted in real-time situations. This forces designers to choose between systems that provide high-resolution, wide field-of-view, or long-range sensing, and rarely is it possible to achieve all three in a single system.

These sacrifices are why software-defined LiDAR systems are quickly becoming a must-have for leading designers, enabling on-the-fly control over key sensing parameters such as:

- Beam width: Adjusting from narrow (e.g., 0.1°) to wide (e.g., 2°) to trade range for speed.

- Scan regions: Defining region-of-interest for selective scanning, reducing latency.

- Dynamic range: Using HDR techniques to improve visibility across bright and dark areas.

- Software defined sensing: Configuring the LiDAR to behave like different sensors in different contexts, such as switching from wide-angle obstacle detection to high-resolution pallet identification during a mission.

Within software-defined systems a programmable transmitter enables a new sensing paradigm, breaking the traditional triangle of LiDAR trade-offs and allowing a single physical system to achieve multi sensor performance.

Introducing Programmable Optics

Active metasurfaces, a nano-patterned, planar optical element, are a type of programmable optic capable of steering and shaping laser beams entirely by software without mechanical parts, realignment, or blind zones.

In active metasurfaces, subwavelength features are electrically tunable, enabling dynamic control of the outgoing wavefront. Instead of physically rotating mirrors or switching between fixed emitters, a programmable transmitter can steer and shape light electrically.

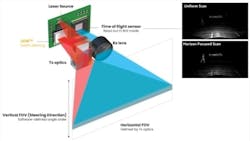

In practice, most LiDAR architectures will use metasurfaces to steer light in the vertical axis, while using optics or lens structures for static horizontal spread. This matches real-world perception needs: scanning across elevation layers while covering horizontal width with wide-angle optics.

One example of this technology that is commercially available and production ready are Light Control Metasurfaces (LCMs), which are CMOS-based flat and field-programmable modules. LCMs can steer light over a wide field of view up to 190° in a completely software-defined pattern (any angle to any angle) with high accuracy and kHz speed. Moreover, they enable beam alignment and control to be managed via software, eliminating the need for mechanical calibration.

By combining LCMs with appropriate laser sources, designers can construct transmitters that adapt in real time, effectively treating the optical output as a software API. Historically, EELs have been reserved for mechanical LiDAR and VCSELs served flash systems. Though both technologies are compatible with programmable optics, EELs gain a new lease on life for solid-state beam-steering lidar systems.

Beam Control in Action

To illustrate the flexibility of programmable transmitters, consider the following example system:

- A laser output is collimated to create a narrow 0.2° divergence line beam spread horizontally 120° using diffuser optics and this line beam is steered across the vertical FoV using a metasurface.

- Now this line beam can be dynamically shaped by software (programming the metasurface) to change the sub-pixel width (0.2°) beam for high-precision ranging to say a 2° beam for fast area coverage.

- Optical power can be concentrated into a single receiver row to detect long-range dark objects or distributed across multiple receiver rows to reduce latency in near-field scenes.

Traditional LiDAR systems are static by design. The scan pattern, field of view, and resolution are determined during development and remain fixed in deployment. This creates rigid trade-offs. This often results in over-provisioned systems with high cost and limited adaptability.

Software Defined Operation in Action

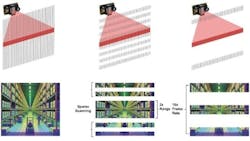

Consider a single sensor used in three distinct modes:

- Spatial awareness mode: Full vertical FoV (e.g. 90°) scanned at 20 Hz.

- Horizon focus mode: Narrow 20° vertical slice with 2x range (longer integration time) and higher resolution. The rest of the scene is scanned sparsely.

- High speed object tracking mode: Three narrow high-speed vertical zones, focused only where objects pass while ignoring empty regions and optimizing scan density.

Such mode-switching can be triggered autonomously based on mission profile, environmental feedback, or operator control—without any hardware change. They are software-controlled scan profiles, delivered through the programmable transmitter that reduce power consumption, improve task performance, and enable flexible allocation of perception bandwidth.

Programmable optics are the only system that provide this flexibility and it enables designers to move beyond static system architectures. As a result, region-of-Interest scanning becomes a powerful tool, enabling dynamically focused sensing effort where it matters and making real-time adjustments based on environment, time of day, or task.

Lighting the Future

The future of LiDAR isn’t just about seeing farther - it’s about seeing smarter.

As 3D sensing moves deeper into the worlds of robotics, industrial automation, and smart infrastructure, the needs are shifting. Systems must be compact enough to integrate anywhere, versatile enough to adapt on the fly, and smart enough to prioritize what matters in the moment. That means turning the old model on its head: where hardware once dictated the sensor’s behavior, software now takes the lead.

Programmable optics make that possible. They’re simplifying system design by replacing stacks of purpose-built sensors with a single, dynamic transmitter - one that can change its scanning pattern, field of view, or frame rate with a few lines of code. And as edge AI platforms get more capable, they’re ready to take full advantage - tuning sensing behavior in real time based on the task at hand.

This is more than an engineering breakthrough - it’s a mindset shift. The next wave of lidar systems won’t just be smaller and faster. They’ll be adaptable, reconfigurable, and aware of the world they’re helping to navigate. Autonomous machines will stop just reacting to their surroundings - and start understanding them.

About the Author

Gleb Akselrod

Gleb Akselrod, founder and CTO of Lumotive, has more than 10 years of experience in photonics and optoelectronics. Prior to Lumotive, he was the Director for Optical Technologies at Intellectual Ventures in Bellevue, Wash., where he led a program on the commercialization of optical metamaterial and nanophotonic technologies. Previously, he was a postdoctoral fellow in the Center for Metamaterials and Integrated Plasmonics at Duke University, where his work focused on plasmonic nanoantennas and metasurfaces. He completed his Ph.D. in 2013 at MIT, where he was a Hertz Foundation Fellow and an NSF Graduate Fellow studying excitons in materials for solar cells and OLEDs. Prior to MIT, Dr. Akselrod was at Landauer, Inc. where he developed and patented a fluorescent radiation sensor that is currently deployed by the US Army. Dr. Akselrod received his Ph.D. in Physics from MIT and his B.S. in Engineering Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He holds more than 30 US Patents and has published over 25 scientific articles.