Barcode imaging saves prison-pharmacy costs

By Lawrence J. Curran,Contributing Editor

In general, prison inmates bring a history of illness with them as they enter incarceration that must be treated with various medications. So, when the prison population in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice reached almost 150,000, department officials sought a more efficient, accurate, and economical way to fill and deliver prescriptions from a central pharmacy to replace the manual methods they had been using. After a detailed survey, they chose a barcode-scanning system that saved about $2 million in its first year of operation. The system has also reduced errors related to drug type and strength by 50% and tripled the rate of clinical interventions.

In a clinical intervention, staff pharmacists evaluate drug therapies by consulting with prescribers to tailor medications to a patient. This study eliminates the likelihood of harmful drug interactions, among other results.

The University of Texas Medical Branch Correctional Managed Care (UTMB-CMC) organization performs much like a large health-management organization. Its Department of Pharmacy serves 150,000 inmates at 140 locations statewide. Pharmaceutical care is crucial because inmate information indicates that about 40,000 have hepatitis C, an estimated 3000 are HIV-positive, and some 170 require kidney dialysis.

The central pharmacy, located at the Estelle Unit (Huntsville, TX), fills and distributes 220,000 prescriptions per month. "Without automation, we would have had to double the number of pharmacists from 30 to 60 to achieve the same degree of care," says Matthew Keith, UTMB director of pharmacy. "By considering an average salary of more than $60,000 for one pharmacist, the automated system represents savings of nearly $2 million a year. We therefore recovered our investment in the automated system in less than a year."

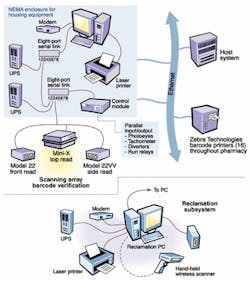

The UTMB Department of Pharmacy contracted with Accu-Sort Systems Inc. (Telford, PA) to design, build, and install an automated sorting and manifesting system based on a three-sided barcode-scanning array, a small-item sorter, and a manual reclamation station. Doctors, physicians' assistants, and other physician extenders at each of the 140 prison sites submit patient prescriptions via terminals that are connected by an Ethernet to an IBM Corp. (Armonk, NY) 3090 host computer at the central pharmacy (see Fig. 1). Staff pharmacists review the prescriptions before releasing them to one or more of 12 filling stations, where technicians select 30-, 60-, or 90-unit blister cards that have been prepackaged on filling equipment provided by Medical Technology Systems (Clearwater, FL). After filling, the blister packages are labeled, checked, and verified by a pharmacist before barcoded labels are attached.

After picking the proper medication, filling-station operators apply barcoded labels to the packages. The labels contain human-readable and barcoded data that include patient information, such as type of medication, strength, dosage, and cost, as well as patient name and location by prison and region (see photo). The barcoded labels are produced by Zebra 90 printers from Zebra Technologies Corp. (Vernon Hills, IL) installed at the picking stations. These stations serve as the locations where barcode-labeled blister cards await loading onto a conveyor belt for sorting and distribution.

FIGURE 1. Inmate prescriptions are entered at terminals at each of 140 facilities in the Texas prison system for delivery to the mainframe host (top right) at the central pharmacy. The pharmacy's sortation interface PC (top left) accepts data sent over a serial link by three scanners to match the medication and patient barcodes on blister cards passing underneath the scanners. This PC guides verified cards to the proper shipping lane, where the card is dropped into a tote container for delivery to patients' facilities. The reclamation PC, scanner, and RF scanner (lower left) comprise the reclamation station. Here, information such as medication expiration dates and cost determine whether returned medications are destroyed or reclaimed.

Labeled cards are manually placed on a conveyor belt, which moves the cards to the integrated sorting and manifesting system. This station includes a three-sided scanning array, a small-item sorter, and a manual reclamation station (see Fig. 2). At the scanning array, a Mini-X laser-based omnidirectional scanner mounted over the belt provides omnidirectional scanning to read the blister-card labels regardless of their orientation on the belt.

The scanning system is unable to read some nonprescription items, such as eye ointments and vials of vaccine, because these items are too small to be sorted automatically or their barcode is in a location that the system cannot read. But, Keith adds, the initial system design didn't require this capability. Instead, the system was designed for blister packages, "and we didn't address the smaller-item challenge until the blister-package solution was successfully demonstrated." Currently, the automated system can sort 80% of non-blister-carded items.

Packages are placed on the conveyor so that their two barcodes can be read by one of two Model 22 scanners. One scanner reads and decodes barcodes on the end or front surface, while the another scanner incorporates a vibrating-vane feature for reading barcodes in "picket-fence" orientations on the side. The patient label on these items is usually placed on the top surface for easier reading by the Mini-X unit. Each unit in the array operates at 500 scans/s.

The omnidirectional scanner incorporates a laser diode, optics, photoeye detector, and a brushless dc motor/mirror wheel. It also includes two serial ports along with input connectors for the photoeye detector and a tachometer. The tachometer provides a pulse that later guides the package to its proper lane. The side- and front-scanning units are both medium-range barcode scanners. They use a RISC microprocessor to decode scanned data at a standard speed of 500 scans/s, with optional speeds as fast as 1200 scans/s available.

In operation, prepackaged medication blister cards are labeled for top reading. The scanning array ensures that the discrete data fields in the prepackaged drug and patient barcode labels match. This verification eliminates the need for final inspection by a pharmacist after an order has been picked and sorted. The verification process is performed by a Compaq PC, called the sortation interface PC. This computer accepts and verifies data from the scanners over a serial link. If there isn't a match between the medication and patient barcodes on the blister card, the PC directs the card to a reject station.

Gary Greiner, Accu-Sort's manager of pharmacy solutions, says that before the automated system could be used, UTMB-CMC had to obtain a waiver from a state law requiring that a pharmacist perform the final inspection of all prescriptions going to correctional institutions. That procedure was a slow and inefficient use of pharmacist skills. Now, instead of laboriously inspecting prescriptions at that stage, pharmacists are more suitably involved in the intervention process.

An 18-month demonstration of the system convinced the Texas State Board of Pharmacy that it could reduce errors and increase the number of clinical interventions the pharmacists could provide versus the manual procedures the system supplanted. The waiver was granted.

Custom softwareThe custom-design Accu-Sort system software sorts prescriptions based on a user-programmed assignment table. This table first translates the prescriptions by wave or lot number and prison unit and then places the prescription package into one of 39 shipping lanes.The software acknowledges each package, tracks the medication to the correct assignment lane, and sorts it into plastic totes for packing and courier transport or into cartons for air shipment. If the information on the labels does not match, the item is diverted to a reject lane for manual inspection and reprocessing. "No-reads" are diverted to a preassigned lane or dropped off the end of the line to be resorted.

"The scanning array operates as a verifier that checks the data fields in two barcodes to make sure there's a match [between medication and patient]. It then asks the [sortation] PC to indicate which lane should get the package," Greiner says. If there's a match, the PC assigns a shipping lane. Positive verification is provided by a combination of the tachometer pulse and the photoeye hits.

The UTMB facility processes five lots or waves of totes for shipment twice a day. At the end of each wave, the system generates printed manifests for attachment to each tote being shipped to a prison. The UTMB also generates barcoded license plates for each prison unit in the statewide system. Using a hand-held gun-shaped RF scanner, technicians match the unique tote number barcodes to the lane-destination barcodes on the sorter (see Fig. 3). The wireless scanners used for lane assignments are linked to the sortation PC; other RF scanners use a wireless link to the reclamation PC.

Once the prescriptions arrive at their destinations, prisoners go to dispensing windows to receive them. About 40% of the medications are returned to the UTMB for re-use or destruction. "Returns are attributable to inmates moving or being released, noncompliance, or prescription changes," Keith says.

Accu-Sort has provided a separate station for the UTMB to process medications for reclamation. An operator at the reclamation station scans the barcode on the card and enters the count on a PC or hand-held Symbol Technologies Inc. (Holtsville, NY) PDT 3100 "destruction gun" for medications that have expired. The PDT 3100 is essentially a barcoded-data-capture terminal.

"We've been running the [barcode-scanning] system for two-and-and-half years," says Keith. "We believe we were the first, and remain the only, pharmacy operation, private or public, doing this automated scanning."

One of the as-yet unresolved obstacles is how to boost throughput for reclaimed medications. Accu-Sort has designed an advanced reclamation solution that uses CCD cameras to image "push-throughs," which are packages with holes where a pill has been punched out of a blister card.

Company InformationAccu-Sort Systems Inc.Telford, PA 18969Web: www.accusort.comCompaq Computer Corp.

Houston, TX 77269

Web: www.compaq.com

IBM Corp.

Armonk, NY 10504

Web: www.ibm.com

Medical Technology Systems

Clearwater, FL 33762

Web: www.mtsp.com

Symbol Technologies Inc.

Holtsville, NY 11742

Web: www.symbol.com

Zebra Technologies Corp.

Vernon Hills, IL 60061-3109

Web: www.zebra.com