Spider monkey population monitored by drones with thermal infrared cameras

In another example of how unmanned technology can serve animal conservation, researchers used drones equipped with thermal infrared (TIR) cameras to monitor spider monkey populations in the Los Arboles Tulum residential development, outside Tulum, Quitana Roo, Mexico.

Spider monkeys are categorized as Endangered or Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. They live in the forest canopy, tend to split into subgroups with shifting size and distance among members, and can move among the trees very quickly. These challenges make spider monkeys difficult to count via ground observation. Successful conservation efforts depend on frequent, accurate population counts.

In their study, titled "Thermal Infrared Imaging from Drones Offers a Major Advance for Spider Monkey Surveys," published on March 11, 2019, researchers compared ground surveys of spider monkey population with counts from drones equipped with TIR cameras. The researchers used a TeAx Fusion Zoom dual vision camera containing a FLIR Tau2 640 core infrared camera with 19 mm lens, and a 1080p TAMRON RGB camera, mounted side-by-side on a drone via a 2-axis stabilization gimbal to provide camera steadiness during flights.

The drone was a 550 mm quadcopter frame built from extruded aluminum arms and glass fiber plates, with a 10-minute battery-powered flight time. Open-source ArduCopter firmware ran a Pixhawk 2.1 autopilot configured for manual or automatic flight. Grid pattern searches were programmed with the Mission Planner application for ArduPilot.

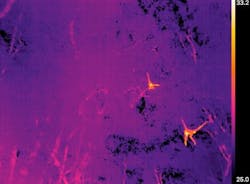

The Tau2 camera was used as a hand-held device for preliminary surveys to determine how the monkeys would appear in the drone footage and to gauge their surface temperature, which was determined to be 30° C. The researchers also generated a typical, 24-hour temperature range for the forest based on several years' worth of satellite observations. They determined that drone flights had to be conducted between around sunset and before sunrise in order to provide the needed thermal contrast between monkey and environment.

Twenty-nine grid pattern searches were conducted over the monkeys' three most-used sleeping sites. Four flights were also conducted in which the drone hovered for a minimum of five minutes over one of the monkeys' sleeping trees. TIR footage was analyzed by an expert in observing warm-blooded animals via infrared imaging. Five experienced observers equipped with binoculars and GPS units conducted ground counts.

The study found that for subgroups of fewer than 10 spider monkeys, ground and drone counts were generally in agreement. Where counts of subgroups of more than 10 spider monkeys were concerned, however, drone counts were higher than ground counts in 92% of cases. In addition, 75% of cases in which ground observers missed monkeys in large subgroups occurred at one of the sleeping sites where view from the ground is more obscured by vegetation compared to the other sites, an issue that did not affect the drones and TIR cameras. The mean increase of number of monkeys detected by drone flights versus ground observation was 49%.

The researchers pointed out challenges for future studies. Heterogenous vegetation and climate can affect population counts and would have to be controlled for. TIR imaging could mistake mothers and huddling children as a single heat signature, whereas a ground observer could make the distinction. Finally, large-area drone surveys of remote areas could be made difficult by regulations against beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) flights and night drone flights.

(Images used via CC BY 4.0 permissions. The study was authored and copyrighted by Denise Spaan, Claire Burke, Owen McAree, Filippo Aureli, Coral E. Rangel-Rivera, Anja Hutschenreiter, Steve N. Longmore, Paul R. McWhirter, and Serge A. Wich. The licensee is MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.)

Related stories:

Machine learning system and IR cameras mounted on drones successfully identify koala populations

FLIR Systems provides thermal cameras for anti-poaching efforts in Kenya

3D vision system monitors the behavior of pigs

Share your vision-related news by contacting Dennis Scimeca, Associate Editor, Vision Systems Design

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTERS

About the Author

Dennis Scimeca

Dennis Scimeca is a veteran technology journalist with expertise in interactive entertainment and virtual reality. At Vision Systems Design, Dennis covered machine vision and image processing with an eye toward leading-edge technologies and practical applications for making a better world. Currently, he is the senior editor for technology at IndustryWeek, a partner publication to Vision Systems Design.