Graphene detector enables full detection of infrared spectrum

Engineering researchers from the University of Michigan have developed a detector made of graphene that is able to detect the full infrared spectrum.

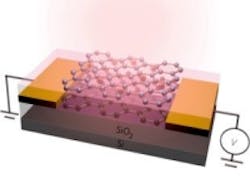

Graphene, which is a single layer of carbon atoms, is able to detect the full infrared spectrum, but because it is only absorbs about 2.3% of the light that hits it, it is not enough to generate an electrical signal. Without a signal, it is unable to operate as an infrared sensor. The newly developed detector amplifies the electrical signal by looking at how the light-induced electrical changes in the graphene affect a nearby current.

This method, as opposed to trying to directly measure the electrons that are freed when light hits the graphene, was achieved by putting an insulating barrier layer between two graphene sheets, with a current running through the bottom layer. When light hit the top layer, it freed electrons, creating positively charged holes, and the electrons performed a quantum mechanical effect that caused them to slip through the barrier and into the bottom layer of graphene.

The remaining electron holes left behind in the top layer produced an electric field that affect the flow of electricity through the bottom layer, and by measuring the change in current, the team was able to deduce the brightness of the light hitting the graphene. This enabled the room-temperature graphene device to compete with that of cooled mid-infrared detectors for the first time, according to the University of Michigan press release.

The research team has already been able to produce an infrared sensor the size of a contact lens, and according to Zhaohui Zhong, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Michigan, the detectors could be used in infrared cameras.

Such a device would obviously not require cooling equipment, but would it work as well as cooled mid-infrared detectors? Apparently so—according to the researchers—who suggest that the device has nearly the same sensitivity as cooled sensors and could be used in military and defense, biomedical and medical, scientific research, or consumer applications.

The research performed by the engineers, which was supported by the National Science Foundation, was published online in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

View the press release.

(Via IEEE Spectrum)

Also check out:

NASA telescope observes evidence of creation of the Universe

sCMOS cameras target scientific applications

UV lighting targets machine vision applications

Share your vision-related news by contacting James Carroll, Senior Web Editor, Vision Systems Design

To receive news like this in your inbox, click here.

Join our LinkedIn group | Like us on Facebook | Follow us on Twitter | Check us out on Google +

About the Author

James Carroll

Former VSD Editor James Carroll joined the team 2013. Carroll covered machine vision and imaging from numerous angles, including application stories, industry news, market updates, and new products. In addition to writing and editing articles, Carroll managed the Innovators Awards program and webcasts.